Information on all upcoming and past screenings is available here.

With a voice born in the mountains and shaped by the hard times she lived and saw, Ola Belle Reed established herself as an influential musician, singer, and songwriter of old-time mountain music. The new documentary, “I’ve Endured:” The music and legacy of Ola Belle Reed”, explores the life of this remarkable musician, singer and songwriter whose contributions have left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape. Ola Belle’s powerful voice and lyrics spoke authentically of her rural roots, and her passionate songs found a home in the folk-revival movement of the 1960s and beyond. She left an enduring legacy. In 1986 Ola Belle received a NEA National Heritage Fellowship. The Library of Congress added her 1973 album Ola Belle Reed to the National Recording Registry in 2019. Her recordings are also preserved by the National Council for the Traditional Arts. Her songs have become anthems of Appalachian life, and she is widely recognized as one of the most influential bluegrass, folk and old-time musicians of all time.

The story told in “I’ve Endured” is one that resonates with themes of resilience, creativity, diversity and cultural significance. The film was produced over the last four years, weaving together archival photos, recordings and newly restored film footage of interviews and performances to present a portrait of Ola Belle, shedding light on her significance and that of the mountain culture she embodied. New interviews with those who knew her, worked with her and were influenced by her, are combined in the film to bring the past, present and future together in conversation. Production was based at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and was funded by Maryland Traditions, a part of the Maryland State Arts Council.

The film was originally produced to accompany an exhibition at UMBC’s AOK Library and Gallery. Ola Belle Reed: I’ve Endured contextualized her achievements within a history of migration from rural Appalachia north in the twentieth century. The exhibit included photographs, concert flyers, instruments, audio, video, and memorabilia drawn from the Maryland Traditions Archive at UMBC.

Ola Belle’s story mirrors that of more than 20 million southerners, who migrated to the north and west in search of work between 1900 and 1980. This great migration, which James N. Gregory has termed the Southern Diaspora (2007), transformed American popular culture, particularly in the area of music. It was instrumental in the development of Blues, Jazz, Gospel and R&B, as well as Country and Hillbilly music. Migrating from one rural setting to another on the Pennsylvania-Maryland border in the early 1930s, Ola Belle and her family brought with them the music and traditions of the New River region of Ash County, North Carolina. Her grandfather Alexander Campbell had been a Baptist preacher and a fiddle player. Her father, a school teacher and shopkeeper, formed a family string band. As a child Ola Belle learned to sing Appalachian ballads rooted in the traditions of England and Scotland from her grandmother and mother. When her brother Alex returned home from World War II he joined Ola Belle in the North Carolina Ridge Runners and other bands in recording and performing until the 1960s.

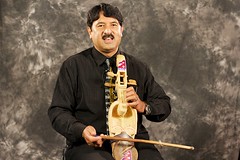

Ola Belle played the old-time style of clawhammer banjo, associated with the Appalachian south. In addition to her musical talents, she became an accomplished songwriter, speaking of Appalachian life and traditions. Following their move to the north, the Reed family performed for audiences largely comprised of other migrants in the Mason-Dixon area, with live radio broadcasts originating from the family store at Campbell’s Corner near Rising Sun, Maryland and live performances at their New River Ranch country music park.

Ola Belle’s central role in the revival of old-time and bluegrass music gained national recognition in the 1970s-1980s. She appeared with her husband Bud and son David at the 1972 National Folklife Festival in Washington, DC. In 1986 Ola Belle received a NEA National Heritage Fellowship. The Library of Congress added her 1973 album Ola Belle Reed to the National Recording Registry in 2019. Her recordings are also preserved by the National Council for the Traditional Arts.

This project is funded in part by Maryland Traditions, the folklife program of the Maryland State Arts Council. For more information contact Bill Shewbridge at shewbrid@umbc.edu.

For more information about the project please visit…

“I’ve Endured”: The music and legacy of Ola Belle Reed

A new 45 minute documentary exploring the life and work of nationally recognized bluegrass and old-time musician Ola Belle Campbell Reed.

“I’ve Endured”: A concert honoring the music and legacy of Ola Belle Reed

View photos and information from the June 2, 2023 concert.

Featuring Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer, the Honey Dewdrops, David Reed, Hugh Campbell & friends w/ M.C. Cliff Murphy

Ola Belle Reed Film Gallery

Short documentaries, performances and extended interviews collected during the production of the “I’ve Endured.”

UMBC Albin O. Kuhn Gallery – Ola Belle Reed: “I’ve Endured”

March 27—June 30, 2023

UMBC Albin O. Kuhn Gallery

Exhibition celebrates this singer and songwriter of old-time mountain music.